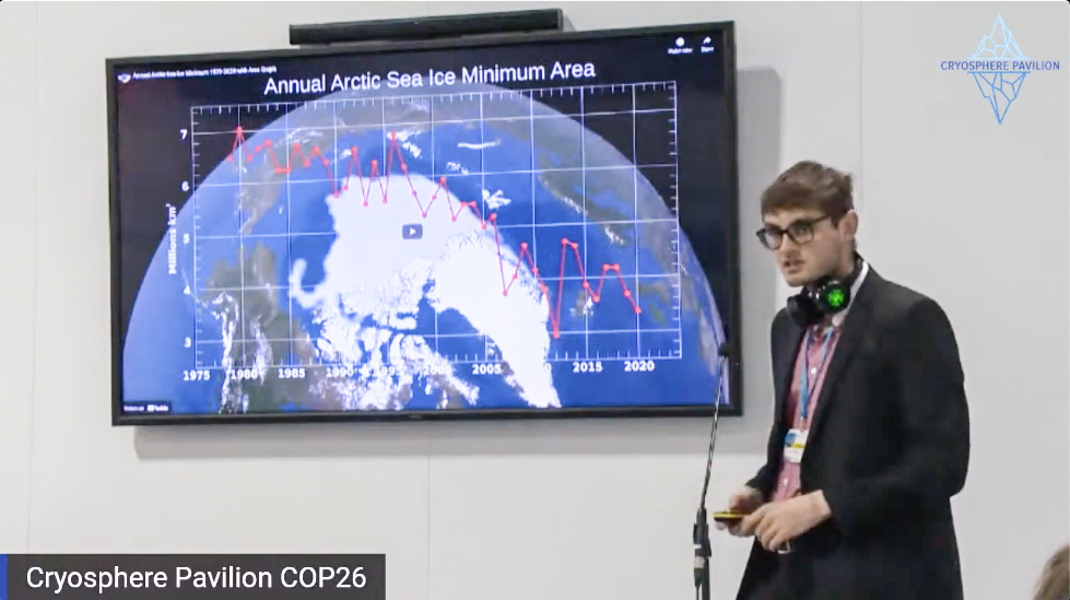

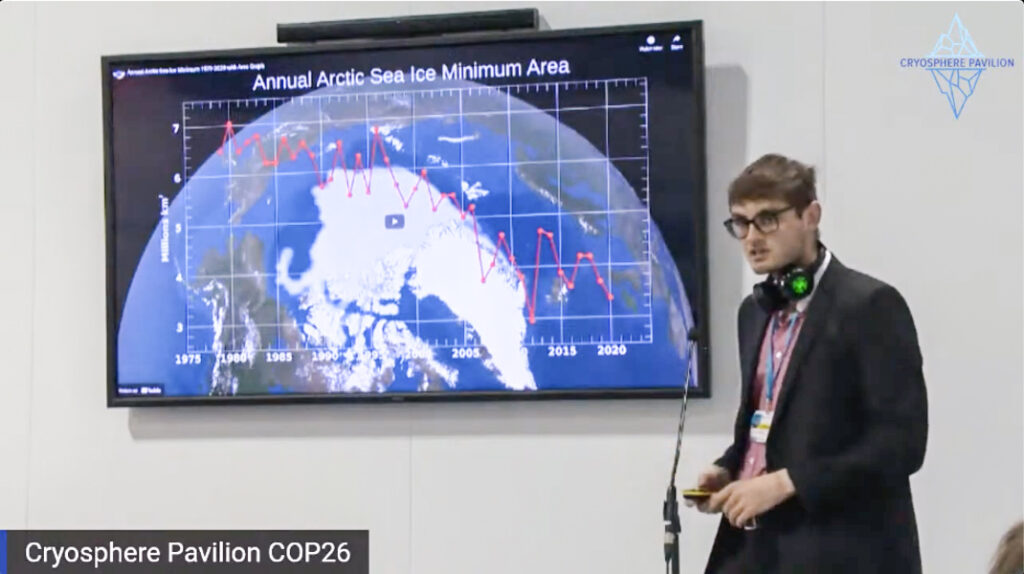

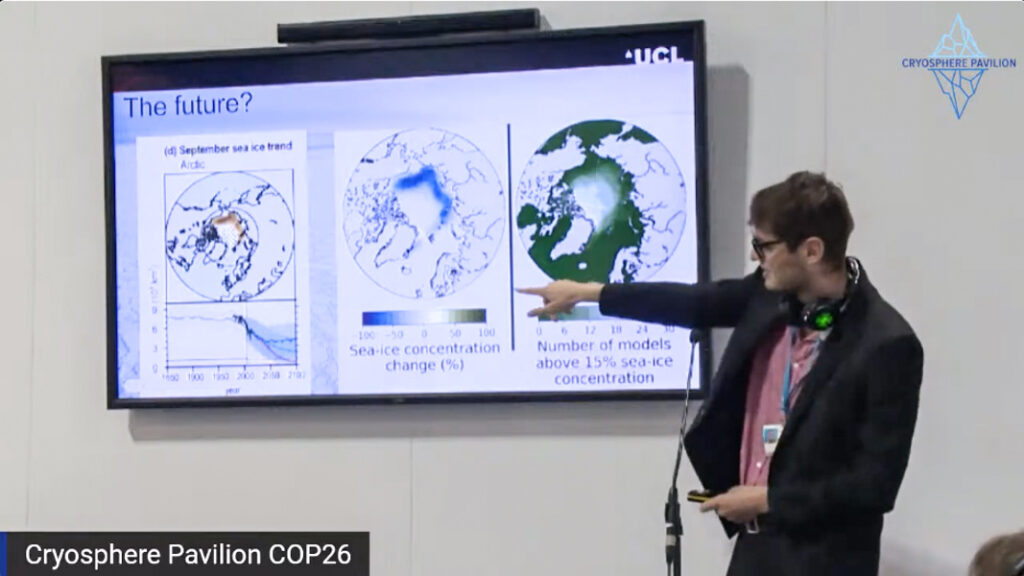

Robbie Mallett, a PhD student at the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling, University College London, spoke to Sam Cornish about his experience in the Cryosphere Pavilion at COP26 in Glasgow.

What was the Cryosphere Pavilion and why was it at COP26?

COP26 is not just for politicians, it’s also a chance for scientists, particularly from the IPCC to communicate with those politicians and policymakers, and to try and synthesise their fields into the policy relevant bits. And there’s a huge conference hall, the size of a huge warehouse, where there are lots of individual rooms called pavilions. Most countries will have pavilions, but also large organisations like the world bank and the WWF will have a pavilion. The recent trend is for big issues to have a pavilion. So there is a pavilion for methane now, there’s a pavilion for wind energy. And starting in COP25 there was a Cryosphere Pavilion. That’s a hangover from COP25 originally being in Chile—Chile has particular cryospheric problems because it gets lots of its water supply from mountain glaciers. When COP25 moved to Madrid they still weirdly had a Cryosphere Pavilion, and it was so popular that they decided to do it again at COP26.

Do you think it’ll stick around?

I think so. The Arctic Ocean is mostly outside national boundaries and of course Antarctica is in some ways exclusively outside national boundaries. So when you have an organisation like COP, like the UNFCCC that’s predicated on nation states, it’s really easy to forget the cryosphere. So it’s good to have a physical presence there. And also, the cryosphere is a nice focal point because a lot of the fault lines in the negotiations at COP are income-based: you have high-income vs low-income countries. Whereas the cryosphere is a really interesting way that you can tie across income lines, for example Bhutan and Switzerland both have melting glaciers and water supply concerns that they can bond over.

one of the most armageddon-like scenarios comes from the crysophere… a mechanism called ice-cliff instability

I heard that the cryosphere was one of the things that people from the policymaking community asked the most questions about, regarding climate reports.

Yes, and that’s definitely because one of the most armageddon-like scenarios comes from the cryosphere, in that the biggest sea-level rise comes from a mechanism called ice-cliff instability that is hotly contested and potentially a massive existential threat. An ice-cliff instability scenario would truly sink big countries. So yeah, there are a lot of natural questions from people who look at the IPCC summary for policymakers and go—“oh what’s that line at the top [of the uncertainty range]?”

It makes sense that politicians would want to seek out experts in a setting like the Cryosphere Pavilion. But did you find that politicians came to the pavilion?

I’d say in the pavilion, by dint of where we were, we were less engaged with politicians than we were with policymakers. So the negotiators, between negotiations, would come and peruse—its almost like when you go to an exhibition, there are exhibition booths and you just walk round and get all the free stuff—and it was our job to coax them in, and actually imprint on their minds the key issues of the changing cryosphere. We weren’t really attracting big names, because the big names weren’t finding space between negotiations to come to the pavilion. That’s the unfortunate reality. But we did have some pretty high-level people from Brazil, and Luke Pollard, the UK Shadow Environment Secretary came.

So it was more policymakers than politicians?

We were there mostly for the policymakers and negotiators. And also just to put a bit of pressure on, as well. I’ve really come to appreciate the difference at COP between when as scientists we’re trying to motivate and when we’re trying to inform. If you’re trying to inform, then you’re doing facts and numbers and graphs. And if you’re trying to motivate, then you definitely shouldn’t be doing that, you should be doing stories.

That’s really interesting. Did you get any kind of training before you went?

We did a course in scientific communication run by the University of West England, that was really interesting. In that we really focused on the difference when you’re talking to journalists, policymakers and the public. They all have quite different needs.

It’s good that they prepared you. These are potentially quite important intervention points, aren’t they?

Yes, potentially, if you can really move the dial on a policymaker by 1% that could be the tipping point between them phasing out and phasing down, right?

How did you get involved?

Essentially UCL is one of the observer institutions to the UNFCCC. And it goes to COP and it sends delegates to COP to give the process legitimacy—a transparency and an informedness that only comes from having independent experts and observers come in. So I was selected as part of the UCL delegation. And then I volunteered at the Cryosphere Pavilion, to best put what skills I have to use. My COP was basically entirely spent around that one room.

Almost all the pavilions had to operate in a bizarre silent disco mode

Ok, so tell us what you were doing in that room.

We had to be quite flexible. There was almost always a talk on, and talks require introductions, moderating and compering. Almost all the pavilions had to operate in a bizarre silent disco mode, where you would have silent disco headphones and listen to the speaker because the whole environment was quite noisy. So we had to manage that system. We were also live-streaming to two in-person hubs, and also live-streaming online. But we also had to engage with people at the conference. There were some poster boards with key information from a recent report that the ICCI put out on the cryosphere and its change. We had to tell people about that and explain why the cryosphere was relevant even if they don’t live in a frozen country. And we also each gave some talks ourselves.

Were you talking about your own research?

A little bit. One of my talks was on the relationship between permafrost and sea ice, and how sea ice retreat exposes sub-sea and coastal permafrost. I found out I was doing it at 4pm the night before the morning of that talk. And I also had to give another talk later that day, and only made it home at 10pm – so that was not good! For the other talk I did a double act with Walt Meier from the NSIDC, we gave a talk on current sea ice change and CMIP6 predictions.

Do you feel like you learned about other aspects of the cryosphere by virtue of being there?

Ocean acidification kind of blew my mind. It’s not even necessarily a cryospheric topic, but the polar oceans—and I didn’t know this—the polar oceans are the most affected by it. And what I think was wild was—I always thought of it in terms of dissolving aragonite and dissolving carbonate shells but the behaviour change in prey species that you introduce by acidifying water, even by a tiny amount, is massive.

Who else was in the room?

We also had officials from the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program (AMAP), they are putting out loads of reports on the Arctic and how it’s changing. It’s a bit like a mini IPCC for the Arctic. Whenever I say the Arctic is warming at three times the global rate, that’s them; that’s their piece of information. We had other important scientists, and generally a really big mix of people from COP. Really we were looking to talk to policymakers and influence the people who would negotiate, but also there were lots of activists and people from business there who would have no idea about the physical science of climate change at all. So we had to be careful about communicating in an accessible way but also giving something that important people could really use.

That’s a tricky balance to find.

Yeah, and it didn’t always work. Some talks were too technical for the audience.

This was a COP where science was accepted and we didn’t need a huge contingent of eggheads there to argue the case with numbers

So how do you feel the activities in the pavilion—and I guess the other pavilions—connected to the negotiations?

It certainly was not well connected. You could potentially avoid the pavilions if you were a negotiator, and plenty did. It’s not an easy sell, when these people are busy, negotiating and holding down the fort at home, to say “come on, let me tell you about this glacier in this place that you don’t live.” But we certainly didn’t have any empty talks, so we were always getting through to some people. It’s possible that COP is just too big, and we don’t actually need that many people there. It’s possible that we don’t need as many scientists there. And that’s not to say it wasn’t great for me. But, I think, the priority in many ways has shifted—the science is understood, especially since AR6: ‘unequivocal’ and all of that. This was a COP where science was accepted and we didn’t need a huge contingent of eggheads there to argue the case with numbers.

What did you learn about the COP process from being there?

I went not understanding very much, and I thought that in a couple of days I would get the hang of it, but actually it was far more complicated than I had ever conceived of before. The way that the UNFCCC relates to COP and the way that the IPCC relates to the UNFCCC and all the sub-committees, and the fact that Week 1 COP is actually very different to Week 2, it’s extremely confusing. So I learned a lot, but left with more questions than I went with.

You’re not doing climate action if you say you’re going to do something radical and then get kicked out. [Politicians] are alive to that risk.

I thought a lot about democracy while I was there, and I got more of an insight into what the negotiators are dealing with. A lot of them want to take more action, but they are afraid, rightly or wrongly, that they will not be elected next time, and then their climate action is worth nothing. You’re not doing climate action if you say you’re going to do something radical and then get kicked out. They are alive to that risk. But then we can make an echo chamber around them at COP and get loads of scientists in the room and say “you need to do this, and you need to do this”, and I think that’s ok, but that’s not without a cost. Do I want politicians to go further than their constituencies want them to? It’s hard, isn’t it?

If you were in charge of the next COP, how would you change the participation of scientists from this one?

I’d probably leave it the same. At this COP, scientists had a good year because the IPCC AR6 was presented at COP and ‘welcomed’ whereas last time I think it was just ‘noted’. I was a bit worried about lobbying going on from the pavilions, and I think it’s only a matter of time until we have a geo-engineering pavilion. I would be a bit worried about who gets to run that, and who gets to say that they’re an expert at COP when they’re talking to policymakers. Because you basically just buy a pavilion. It all seems to be ok now, but in the future, I will have my eyes on that.

I was a bit worried about lobbying going on from the pavilions… It all seems to be ok now, but in the future, I will have my eyes on that.

If we are thinking of this as being a sensitive intervention point, then it also matters who’s there, who’s intervening.

Exactly. Especially as there are also some separate side-events, where along similar lines, you can just pay to make a presentation. I think we need to watch that in the future.

Apparently the fossil fuel contingent there was really big—could they do a side event or have a pavilion?

No I don’t think they could, I think the presidency would be able to block that. But it’s soft, right?

Have any new research ideas emerged for you? Has it helped with your research progression, attending COP?

I find it quite motivating. Particularly the way the IPCC was interacting with the COP process. I’m not sure that this is going to influence the papers I write in the next decade. But it may well influence the papers I write beyond that.

So why maybe beyond that ten years?

I think it’s related to the bottleneck of your research scope as an academic. The scope of your research bottlenecks as you transition from undergrad to PhD, and then you widen out as you become more and more senior, and generally, politicians will listen to you more as well. When you get “Professor” in front of your name, people listen, and then you do more policy relevant work, because you’re not wasting your time when you do it. But yes, if I want to write a paper that’s aimed at the policy community rather than the scientific community, I’ll be much better positioned to do that.